When I first started coding in HTML, HTML itself was a baby. This was about a year before Java, JavaScript, Ruby. All I could really do with it was play around, and my friends and I played around quite a bit in our lunch hour at school in the computer lab. As web 1.0 took shape, we coded up fan pages for the television shows and books we enjoyed, informational pages about obscure Welsh towns with really long names, individual pages for ourselves mostly, I think, for college applications. I remember coding and archive of a group story written via listserv, using small awkwardly rendered images to show who had written what and having a very neat but very ugly menu on one side of the page. It was a simpler time.

Now it’s a somewhat intimidating number of years later, and the web is very different. I’m writing this on the web, for example. I’m writing this in a word processor in a web browser via a dictation program that also interacts with the web browser. The dictation program existed back then, it was called Dragon Dictate, but the browser I’m writing on did not exist and the company that maintains it didn’t even exist for the first couple of years I was tooling around on the web. It’s an interesting world to look at having been poking around at the edges of it at the beginning, and now finally expanding my knowledge of it into things like asynchronous procedure and creating webpages that have a front-and a back-end.

Fetch (and Go)

AJAX stands for Asynchronous JavaScript And XML. It encompasses the asynchronous procedure that allows pages to load with the perception of simultaneity from the user point of view. Typically the first things that render are the styling elements involving HTML and CSS. The HTML might render the static elements either for general background information purposes or for simple styling, and as it states in the name the CSS is the styling of the page. After these initial simple elements that do not require any interaction or resolution to display, the fetch() protocol can begin.

The first part of the fetch() protocol is the request. A fetch request is a global method that acts on the window object and returns a promise object. A promise object exists in one of three states, much like a token in a Go game. Instead of alive, dead, or unsettled the promise object exists in a state of fulfilled, rejected, or pending. Once the promise object is successfully returned, rather than in the state of pending, the functions attached to it can then be performed. For the purposes of this explanation I also use the Go analogy because when a promise object is in either a fulfilled or a rejected state, it is said to be “settled”. It may also be termed “resolved”.

In the game of Go, a stone or group of stones is said to be alive if the player can connected to other friendly stones around the board. A stone or group of stones is said to be dead if it can be immediately captured. In the same way if the promise object is returned in a state of fulfilled, certain functions can subsequently be called and the intended course of the website can continue. If the promise object is returned in the state of rejected, other functions are called and usually the intended course of the website is halted so that the errors can be corrected. The functions are chained to the fetch request by a series of commands using .then. Because these functions are chained, each function can only be called and begin operation when the previous function has three settled to a state of alive, or fulfilled. Otherwise the function must be settled into a state of dead, or rejected, and errors must be fixed (or the board wiped clean) before the function chain can continue.

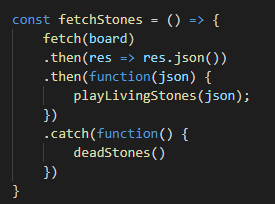

Like a chain of stones, each successive element is connected to the previous one. So in the typical example

the initial fetch() refers to a URL, which encompasses some data. The data reappears in the first .then call, assuming that first promise object is returned alive/fulfilled, and can be named pretty much anything although in this case and in standard format is usually called something like “response” or “res”. The function within the first .then call returns the response data converted into json data. The next .then call in the chain contains another function which manipulates the json data in some way, and if we needed to manipulate the returned result of that function (or set of functions), we could add another .then call, and so on. By usual practice, at the end of all of these comes the .catch call, which handles any dead/rejected promise objects. Since the rejected promise objects are now captured and can no longer be connected around the board, they must be resolved within the catch call. Having done that, as I understand it, other stones can then move around the board meeting that other functions can be called after the .catch call. But at the moment that’s a bit more advanced than my current experience has me comfortable with.